.jpg)

Therma Headquarters

Therma headquarters.

When you ask executives at architectural sheet metal companies to describe the culture of their firms, the question elicits a range of answers.

The first word that comes to mind for Johansen Mechanical Inc. President Keith Johansen is “family,” exemplified by the annual events that his company organizes for employees and their families.

Tom Zahner, chief operations officer at A. Zahner Co., emphasizes the importance of effective communication. Glenn Parvin, the president and owner of CASS Sheet Metal, cites a philosophy of “doing more” — going above and beyond the terms of a deal with a client. And Joe Parisi, founder of Therma Inc., says "you can go out and talk to anybody here at Therma and they’ll all say it’s cooperation that makes this company!"

CASS’s sheet metal workers were proud of being part of the Detroit Red Wings “Arena Team 2017-Detroit-original.”

Executives from a diverse group of architectural sheet metal contractors shared their thoughts with SMACNA about how to promote an effective company culture. Despite the differences in their businesses, a number of common themes emerged in the discussions.

Trust

Carol Duncan, the CEO of Clackamas, Oregon-based General Sheet Metal, notes that productive personal relationships between employees are at the heart of the GSM’s success. The company has more than 250 employees, and she says building trust between them is key. That enables employees to share ideas and have “tough conversations” when necessary, according to Duncan.

McKinstry employees follow safety procedures while installing green girts and insulation on a project.

“Employees have shared that what keeps them at GSM is the people,” she says. “Having positive relationships with their peers and managers contributes to a healthy work environment.”

In an industry like construction, one important way to build trust is by emphasizing safety. For example, Seattle-based McKinstry, which has more than 2,100 staff members and tradespeople working across the United States, prides itself on providing “a world-class safe work environment,” according to Kenny Branson, the company’s business manager for architectural metals.

Communication

Based in Kansas City, A. Zahner Co. typically employs between 110 and 150 people at a given time. That total covers a spectrum of job functions, including designers, engineers, shop manufacturers, construction workers and more. According to Tom Zahner, that means transparency and effective communication are at a premium around the architectural sheet metal company.

“We have people with different strengths who work in different disciplines and kind of speak different languages, per se,” he says. “We need to overemphasize the importance of communicating. It’s a survival mechanism because we have interaction between so many different disciplines.”

Creativity and Innovation

Those new ideas play a vital role in helping companies come up with fresh approaches to their work, according to the executives. They expressed widespread agreement that fostering creativity is paramount in their field.

Johansen Mechanical organizes annual outings for employees and their families like this recent fishing trip to Lake Chelan, Washington.

Innovation takes on even greater importance when it comes to custom manufacturing, according to Tom Zahner.

“I think part of our reputation in the manufacturing and construction world is that we are capable of investigating and working with things that are not necessarily standard,” he says. That innovative spirit carries over to identifying opportunities for process improvement and boosting efficiencies, Zahner adds.

The push to innovate led McKinstry to expand its suite of services and expertise to “provide a single point of accountability across the entire building lifecycle,” according to Branson.

“We see how much energy and time is wasted in our industry, both in the way buildings are built and in the way they run,” Branson says. “Working together creatively to cut that waste — efficiently designing, constructing, operating and maintaining high-performing buildings — is the key to our success.”

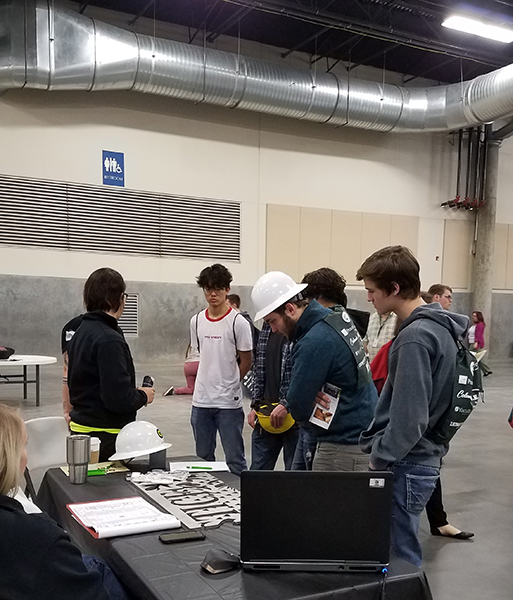

GSM speaks to students at a high school career day.

Executives point to the implementation of new technologies and systems as evidence of the benefits of an innovative spirit. For example, GSM has adopted prefabrication to speed up installations and is using new laser technology to enhance designs.

Giving staff room to breathe and use their brains produces amazing results, says Joseph Parisi, founder of Therma LLC in San Jose, California.

“It’s amazing how much talent some of our people have,” he says. “Most of the time, I allow them to breathe and do their own thing. And it’s been shocking to me, the things that have come out of their brains that we’ve been able to expand upon and use. If you allow your employees a lot of room to breathe, it’s amazing the things that you get paid back with!”

Mentoring and Continuing Education

Innovating requires staying up to date with new techniques and developments in the industry. “As technology is constantly changing, we need to stay on the cutting edge to remain competitive,” says Johansen.

A. Zahner hires architectural interns to work on robotics development.

Johansen’s company offers support and training for employees who want to learn more about the industry. For instance, JMI pays for workers to attend classes offered by SMACNA on the national level. The company also encourages office and union employees to take advantage of training available to them through local SMACNA seminars and the Local 66 training center.

Some companies emphasize grooming employees for managerial roles. McKinstry’s “Fast Track” program identifies high-performing workers and starts preparing them for broader responsibilities via classes, job rotations and mentoring from leaders across the company’s divisions.

At GSM, employees complete questionnaires to help focus their development and take personal ownership of it. The company also holds an annual planning session devoted to setting goals for employee development.

Internships offer another route to attract talented young employees. Zahner, for instance, has refined its internship program over time to serve as a trial run for college and graduate school students.

“We now utilize interns for more value-added tasks,” says Tom Zahner. “We also find that internships are the best way to identify future Zahner employees. We've structured the internships much more, both in terms of the selection of who is going to do an internship and in the way that we measure and observe interns in a professional setting.”

McKinstry prides itself on providing a world-class safe work environment.

Given the importance of skilled trade work in construction, companies also look for ways to support apprentice programs and outreach. GSM employees sit on the boards of multiple workforce development organizations in the local area, including pre-apprenticeship programs that focus on underserved communities.

“This gives us direct access to events where public and private entities collaborate and have meaningful conversations about how to bring job seekers and businesses together,” Duncan says.

Ultimately, executives say, their main goal is to instill a sense of pride in their employees for the work they do. That’s why CASS Sheet Metal, which is headquartered in Detroit, pushes employees to exceed clients’ expectations on every project, according to Parvin.

“When people are allowed to do a high-quality job, they take extra pride in it, and that builds on itself,” Parvin says. “That’s what we’ve tried to instill in our employees, and it has worked for us for nearly 30 years.”

A. Zahner »

CASS Sheet Metal »

General Sheet Metal »

Johansen Mechanical »

McKinstry »